Monday, November 13, 2006

Credit where credit is due

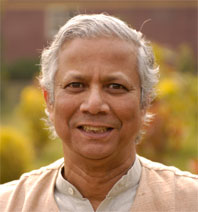

The face of microcredit today, quite rightly, seems to be Muhammad Yunus, the founder of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and a man who certainly puts his money where his mouth is. It's pretty incredible that microcredit is getting attention in the mainstream media at all these days, and I think that is a testament to the strength of this idea and its ability to empower people living in poverty. The concept rests on giving small loans to the poorest of the poor by using community as collateral, and Yunus and the Grameen Bank won the Nobel Peace Prize this year in recognition of their work to empower millions.

Action, of course, brings us further than words, and in the 1970s Yunus, an economics professor at University of Chittagong, realised the credit and finance policies he was talking about in class had a direct impact on the people on the other side of that classroom door. He believed that inability to obtain credit and loans from major lending institutions was a major obstacle to people being able to raise themselves out of poverty - an 'unfreedom,' as Amartya Sen would say.

Action, of course, brings us further than words, and in the 1970s Yunus, an economics professor at University of Chittagong, realised the credit and finance policies he was talking about in class had a direct impact on the people on the other side of that classroom door. He believed that inability to obtain credit and loans from major lending institutions was a major obstacle to people being able to raise themselves out of poverty - an 'unfreedom,' as Amartya Sen would say. The way to overcome this, he believed, was to turn the traditional lending relationship on its head. Women were being regularly turned down for loans by big banks for lack of physical or monetary collateral. The only other option was to borrow from exploitative loan sharks, who often charged enormous interest rates that women were unable to pay back. The alternative, he suggested, was to see community support as a form of collateral in itself. How this plays out is that one can borrow a relatively small loan (an average of $75 US) on the condition that a group of about 4 other people in the community agree to pay it back if one is unable to or is late making payments. My good friend Wikipedia describes the advantages thusly:

Each group of five individuals are loaned money, but the whole group is denied further credit if one person defaults. This creates economic incentives for the group to act responsibly (such as other members then being able to receive additional loans), increasing Grameen's economic viability.It keeps the borrowers accountable to the lender as well as to the community, and the relatively small amount of money available through microcredit ensures that they are manageable sums to pay back, although they may make a big difference. The Grameen Bank, or something approximating 'rurual bank' in Bangla, focusses specifically on providing loans to women at the bottom rungs of poverty; I have heard this criteria characterised as, essentially, if they have a bed to sleep on instead of a mat, or a well nearby instead of in the next village over, they're not poor enough to be eligible.

The emphasis on women is intended to be a means of empowerment in itself, and they are also considered to be more reliable borrowers than men, since their responsibilities to children are greater, making them less likely to squander the money and more likely to make higher return investments. As the Grameen Bank allows borrowers to gradually borrow more each time they repay a loan, it helps women running small businesses out of their homes expand in small, practical steps towards a future out of poverty. They also claim to have an incredible payback rate of between 97 and 100%, which is, well, unheard of in conventional lending relationships with major financial institutions. I should say, though, that this figure's reliability is often questioned.

I say all this out of what I have learned, the people I have talked to, the videos I have seen and the articles I've read. I haven't seen for myself how microfinance works on a community level, and I've heard some criticism of Yunus that although he founded the Grameen Bank 30 years ago out of that moment of connection between the classroom and the villages, Bangladesh continues to be one of the poorest countries in the world on a national level. A speaker from another microfinance organisation spoke to one of my development classes last year, and explained her organisation's methods of lending. She made it clear that they weren't a charity, and that loans were only available to women who were already running small businesses, whether this be selling eggs or ice out of a small freezer. In most of sub-Saharan Africa, she said, this was a moot point because almost every woman ran small businesses like this to make extra money for schooling, for medicine, for food.

We dug into her pretty viciously though, about why microcredit borrowers are required to pay interest at all and whether the loans worked toward goals of sustainable development on any meaningful level. Okay, that last part was mostly me, asking whether her organisation (which I won't name at the moment) was looking past simple economic sustainability to environmental considerations too - for example, looking at where the energy to power that freezer came from (and I should have brought up social sustainability as well). Her answer was basically that it was that the number of borrowers was so small and their impact so minimal on the environment that no, that didn't come into play.

In terms of interest... well, all microcredit organisations, from what I gather, charge interest at differing rates (the Grameen Bank's is about 20%), but those profits go right back into funding further microcredit operations and making more credit available. They are also generally much less than those at major financial institutions or the 50% or higher demanded by loan sharks. It could be seen then, as something of the poor helping the poor. An inverse Wal-Mart, almost.

Personally, it seems that Yunus' goal of eradicating poverty through making credit universally available is unattainable. The mechanics of our global socio-economic system rely on the poverty and exploitation of some to provide the wealth and luxury others, including myself, have come to see themselves as their entitlements. As well, the Grameen Bank has been criticised for not being truly economically sustainable, since it relies on subsidies and grants to make up a significant amount of its finances. Perhaps I'm being too cynical. As I say, I have no direct experience with women who have benefitted from access to microcredit, so who am I to criticise?

And now this week, Canada's Foreign Minister, Peter MacKay, announced that Ottawa is committing $40 million to to microcredit operations in other countries. On the one hand, the Third World is right here in Canada too, and Ottawa should have allocated money for microfinance here at home as well. On the other hand, you have to give them credit for having the guts to support a concept as seemingly radical as this. Peter MacKay seems like an alright Foreign Minister to me, purported dog comments aside, and I really think the Conservatives ought to be commended on this occasion for supporting intitiatives that genuinely benefit those living in poverty beyond our borders. It's not a lot, but it's a step, and I think that's the idea.

One thing I am very interested in is the Chinese government's interest in allowing microcredit lenders to set up shop in their country. Apparently they've asked the Grameen Bank for help setting this up. Somewhat hilariously, I've read the that Grameen Bank specifically recommends that governments stay the hell out of the business of microlending and leave it to smaller institutions. Now, in case you hadn't heard, I'm headed to Chengdu in the spring. Does anybody happen to know someone I could um... hook up with while I'm there or even, I don't know, Muhammad Yunus?

Labels: canada, empowerment, poverty

posted by Christopher at 1:05 a.m.

0 Comments:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.